In 2014, news that Nigeria, Africa’s biggest country in population size had overtaken South Africa to become Africa’s biggest economy reverberated throughout the African continent. Finally, it was thought that Africa’s population behemoth had arisen to take its place atop Africa’s states economic perch. After rebasing the base year from 1990 to 2010, the Nigerian nominal GDP went from 270 billion U$D to 510 billion U$D well above South Africa’s GDP of 350.26 billion U$D. Since then Nigerian economy has flown into severe economic headwinds that have left analyst wondering whether the new found optimism in the country was a tad too early.

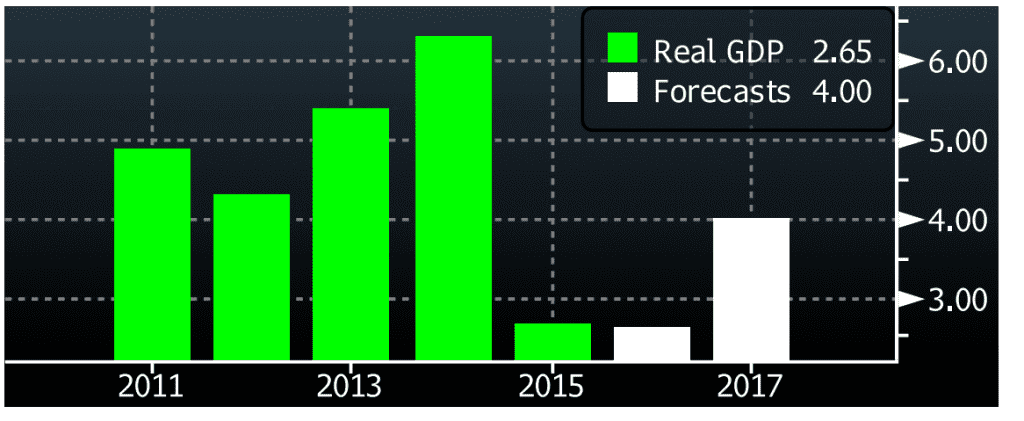

Since the global oil price down, oil exporting countries have suffered severe economic challenges, none so than the countries like Venezuela and Nigeria, which have had economic non-diversification strategies with oil exports as national bread and butter. This oil or commodity based GDP growth has its own inherent challenges. In 2015, Nigeria recorded the biggest GDP growth rate drop in years, with a GDP growth of 2.8 %, in the same year inflation hit 9 %. In 2016, growth forecasts cap GDP growth at 2.4%, the lowest growth rate in a decade, and inflation in the first quarter of the year has already hit 12.8%.

Nigeria’s Slowing GDP Growth

Source: Bloomberg

Slow growth and increasing inflation are having two conceivable effects on the country’s population. The country’s estimated 73 Million people who live below the poverty are being priced off the market for the purchase of essential items like food; secondly, it is putting a noose on the spending power of the growing, consumerist middle class which had been christened as the engine of Nigeria’s growth. Before the slump down in oil prices; Nigeria was dependent on oil for 75% of its public budget and 95% of its total exports. After the onset, Nigeria’s current account deficit has grown to 2013.9 U$D million from a surplus of 6880.29 million U$D in January 2013. The government is also suffering from severe fiscal constraints, this year the economy run a budget deficit of 15 Billion U$D or 3% of GDP. This budget deficit is bigger than some bigger than the GDP of some African countries such as Malawi.

The slowdown in global Oil Prices has led to increasing Current Account Deficits in Nigeria

Source: Bloomberg

Earlier this year, Nigeria requested for a 3.5 Billion U$D loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to shore up its budget deficit. The irony being that exactly a decade ago, the then-president Olusegun Obasanjo made a big thing of the country weaning itself off international debt.

Nigeria’s monetary policy is not helping the situation. A bout of foreign exchange controls, monetary nationalism, and imprudent monetary policy has severely dented confidence in the Naira. The Naira has lost 25% of its value against the dollar since the beginning of 2014. President Muhamadu Buhari has been resolute in his quest not devalue the Naira, despite advice from technocrats in the Central Bank of Nigeria. The official interbank rate is 200 Naira for 1 U$D whereas the black market rate is 325 Naira for 1 U$D. Nigeria’s quest to achieve the impossible trinity of free capital flows, fixed exchange rate and independent monetary policy. Corruption and waning confidence in the economy have led to increasing capital flight, leaving analysts worried that erratic monetary policy would bring the country’s economy to its knees.

The question policy analysts should be asking though is how Nigeria, a country with enormous human capital potential has become a one-trick pony economy dependent on oil as the holy grail of economic development. Nigeria, perhaps; is the class embodiment of the Dutch disease when the oil boom was at its peak when a barrel of oil was retailing at 125 U$D the first half of the Nigerian economic miracle was being written. What most people failed to see was that Nigerian growth had been predicated on a single commodity rather than an all rounded dynamic economy. Consequently, the oil boom obscured policy makers from channelling investments and policy focus in other industries in the economy which would have come in handy in the wake of erratic oil prices. This under-investment in sectors other than oil has led to relatively underdeveloped sectors like manufacturing and agriculture, which is appalling considering that Nigeria has the biggest domestic market on the continent.

Whereas the current slowdown in the global oil prices presents surmountable fiscal and monetary challenges to the Nigeria economy, the country could use this opportunity to diversify and dynamize its economy. Investment and appreciation of human capital and the role human capital has to play in the economic development of the country could see the country reap its population dividend. However, that to is not enough, the restrengthening of critical institutions such as the rule of law, the withering of an extractive political system, deregulating the business environment and a conscientious fight against corruption could see the country finally live up to its economic expectations, finally?

Save