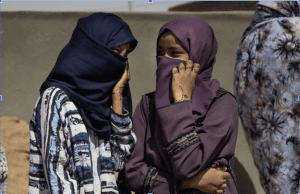

Gender dynamics and female identity in Sudan are intriguing topics as they are shaped by the social and economic realities of being one of the world’s poorest countries. Contrary to what some could think, however, the social position of women is not characterized by oppression or discrimination.

To get a better understanding of what being a woman in rural Sudan means, in June I visited three villages in the north: Abri, Amara, and Serkamato.

Although I ascertained that gender roles in rural areas are highly patriarchal, with men responsible for providing economically for their families and women being homemakers, practically all women I interacted with were satisfied with the existing social order.

For most Sudanese living in the north, family is the most important aspect of life. Families are multigenerational, and village communities are often made up of extended families. Everything seems to be revolving around preparing for and celebrating weddings and childbirths.

While polygamy is practiced only in certain parts of Sudan, in all the villages I visited men are free to marry multiple women. Some have up to four wives and multiple children with each of them.

As marriage typically involves payment from the groom’s family to the bride’s, some enter into relationships in hopes of improving their economic situation. Nowadays love marriages are becoming increasingly popular, however.

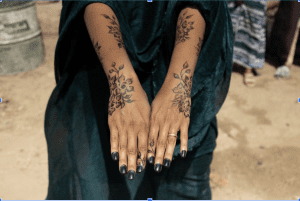

Sudanese weddings, which last several days, are characterized by beautiful ceremonies in which entire villages are involved. In preparation for the wedding, women put henna on their hands and feet. Women also cook together, making food for what often adds up to more than one thousand guests. Actual celebrations take place in the evening and anyone from the village can join and participate in eating and dancing.

Sudanese weddings are joyful and are an opportunity for everyone living in the village to come together and build a sense of community. This is particularly important in Nubian towns such as Abri where numerous ethno-linguistic groups coexist. The Nuba people speak different languages and have their own music, traditions, and culture, so events such as weddings play an important role in preserving their heritage.

With family being perceived as the center of life, people take pride in having many children. On average, families have five children, but in older generations, it is not uncommon for people to have ten or more siblings. Typically, there is a preference for boys.

‘When a girl is born we slaughter one goat to celebrate, when we have a boy, we slaughter two,’ I was told.

One of the reasons why people in rural Sudan have so many children is that once the kids get old enough, they help their parents make an income, take care of the house, or run a small business such as a stall at a local market.

Although in northern Sudan women’s primary task is to bear children, they are also responsible for building houses. In Serkamato village, for example, most houses are mud huts built using a mixture of sand, water, and animal dump.

‘We put a new layer on the floor every year because it gets thinner over time,’ one of the ladies told me. ‘Now we are doing it because we are preparing for a wedding,’ she added.

Limited employment opportunities are possibly the biggest challenge for families living in rural northern Sudan. Many rely almost entirely on farming to get food as they do not have enough money to purchase products in shops.

‘Life is difficult but we are still grateful to Allah. As long as we have two dates to eat and some water it’s enough,’ said Fatma, aged seventy-five.

Despite obstacles, women I met in the three villages appeared full of optimism and grateful for positive things in their lives, no matter how small these things might be.

Today in Sudan, women’s roles are changing, even in rural areas. People learn about the importance of gender equality and women are beginning to realize that they too, not only men, can pursue their ambitions and be in charge of shaping their future. Having said that, in the villages I got to visit, most women choose to focus on nurturing children and cultivating traditions.

After getting a glimpse into everyday life there, it became clear to me that their voices are not being silenced but that in these communities women find the most happiness in having a family. I found a lot of beauty in their approach to life and I experienced the topic of female identity from an angle that I did not think I would find in rural Sudan.

Katarzyna Rybarczyk is a political correspondent for Immigration Advice Service. She covers humanitarian issues and writes articles raising awareness about the challenges that communities living in low-income countries face.