In 2013, in a Guardian article, celebrated Kenyan author, Ngugi wa Thiongo made an interesting observation. He said that over the years, the African Union (AU) had been reduced to a talking shop instead of a fighting club; invisible within and without and incapable of safeguarding Africa against marauders.

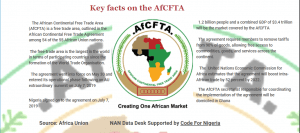

Six years down the line, thanks to the launch of the operation phase of The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) on 7th July of this year, it appears the AU is determined to shake itself out of the long slumber of the past fifty-something odd years. That is not to say the journey of waking up began this year. No. The desire to reinvigorate the AU and realize the body’s full potential started a while back and was galvanized in 2015 with the launch of Agenda 2063. In turn, Agenda 2063 gave birth to AfCFTA.

However, on the heels of the launch, one has to wonder, what does the AfCFTA spell for Africa? Will it be the economic game-changer African leaders think it will be? If so, then why is it that up until now, African states have not aggressively pushed for increased intracontinental trade?

Why has Africa lagged behind with regards to intracontinental trade?

It is common knowledge that Asia enjoys approximately 50 percent intracontinental trade while Europe enjoys 70 percent. The benefits of such expansive trade are visible. Europe boasts of massive economic growth, not to mention, improved living standards and higher salaries for workers. On the other hand, though, the continent of Asia has lifted more people out of poverty in the past few decades than any other continent.

In contrast, Africa, which only has 15 to 18 percent intracontinental trade, has missed out on these benefits. According to the AU Commissioner for Trade and Industry, Albert Muchanga, two key things have hindered intracontinental trade in Africa over the years.

One, during colonization, the colonizers designed Africa to be a major exporter of commodities to the colonial regions. True to that design, Africa mainly exports to the west.

Second, when colonizers were establishing transport and communication channels and networks, they designed them to support and favor the export of commodities to colonial regions and not to other African countries. As a result, the various African economies or countries remained—and still are—isolated from one another.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The AfCFTA agreement states that signatory countries will offer preferential tariffs to other member states according to the agreed-upon tariff concessions guidelines.[/perfectpullquote]

That said, it is essential to note that of the 15 to 18 percent of the trade that occurs within Africa, 42 percent is in manufactured goods. That means the potential for intracontinental trade in Africa is huge, and it is this observation that planted the seed for AfCTFA.

Understanding AfCFTA and some of its key instruments

The idea behind AfCFTA was that if the level of trade between African countries could increase (especially in manufactured goods), and that if the relevant authorities worked at removing the fragmentation or isolation that exists between member states, then it would be possible to create one large aggregate economy that would attract large scale and long term investment.

To that point, the agreement has six integral protocols: trade in goods, trade in services, intellectual property rights protocol, investments protocol, dispute settlement protocol, and competition policy protocol.

When the AU launched the operation phase of the AfCFTA last month, it announced that the five major instruments largely concerned with the protocols of trade in goods and trade in services were almost complete.

Moreover, the announcement confirmed that come 1st July 2020, when actual trading will begin, all these instruments will be complete and ready to operate. Note that instrument, in this case, refers to a legally enforceable process, act, obligation, or contractual duty. The five instruments comprise:

I. Non-tariff barriers

Non-tariff barriers are the barriers that hamper trade through mechanisms other than the imposition of tariffs.

Under this instrument, the adopted framework allows for the identification, categorization, monitoring, and elimination of non-tariff barriers according to the agreed-upon guidelines.

II. Tariff concessions

Tariff concessions allow the removal of duty for certain goods that an importer would otherwise be forced to pay under the tariff. The AfCFTA agreement states that signatory countries will offer preferential tariffs to other member states according to the agreed-upon tariff concessions guidelines.

However, where member states are already members of a given Regional Economic Community (REC), for example, EAC, and where the REC has already achieved a higher level of elimination of trade barriers and custom duties among its members, then the REC agreement will take precedence.

III. Rules of origin

With regards to this instrument, all the goods originating from the member states will enjoy preferential treatment. In an interview with CNBC Africa, Albert Muchanga noted that the AU does not want Africa to become a dumping ground or warehouse. That means whoever decides to invest must produce in Africa and sell in Africa, not bring in manufactured products from elsewhere.

IV. Payment and settlement

The instrument of payment and settlement is concerned with the smooth exchange of money between traders. To that end, the relevant bodies within the AU are in the process of finalizing a detailed digital payment system.

The digital payment system, according to the details divulged during the launch, will operate on two levels—payment and resettlement. The first level will allow or facilitate payments in local currency. In turn, this will reduce the pressure on governments to ensure traders have access to foreign exchange.

For instance, a trader in Ghana who wants to make payments to another trader in South Africa. The Ghana trader can use the local currency, and the South African trader will receive the payment in their local currency.

V. The African trade observatory

The observatory enumerates guidelines on how those interested will access both general and specific information on trade opportunities in the market. For instance, the products and services available for export and import across the market.

What does this spell for Africa?

With the above understanding, especially how AfCFTA will work, it is now time to answer the most important question. How much of a game-changer will the agreement be?

Research indicates that if all the member states fully embrace AfCFTA and work towards making it a success, then the single market has the potential to increase regional trade from 18 percent to 25 percent in the next ten years.

That might seem like a negligible jump, but some analysts will argue that such an increase will greatly improve Africa’s annual economic growth, reduce poverty, and create wealth. Some are skeptical; They call the agreement a laudable effort that will not yield much.

Here is the thing though, Africa does not have much of a choice. In 2018, president Kagame noted that Africa is fast running out of time to replicate the growth strategy that has transformed Asia. Without this agreement, Africa will not be able to catch up with Asia and the rest of the world.

M.W. Muiru is a professional content writer specializing in African issues and technology. Find her on Twitter @MWMuiru.