Freedom is often spoken of in grand political terms: freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, freedom of religion. For millions of Nigerian children living with disabilities, freedom equates inclusion — the ability to play, to swim, to dance, to run, to be seen, and even to simply be included. Yet, this basic freedom remains out of reach for many of these children. They are frequently excluded from extracurricular activities like sports, arts, and school clubs, which robs them of confidence and the social bonds essential for their psychological growth. To address this disparity, Nigeria should invest in inclusive extracurricular education by incorporating disability inclusion into national school policies, teacher training, and community grants.

According to the World Health Organization, over one billion people worldwide live with some form of disability. In Nigeria alone, at least 33 million people have disabilities, many of whom are children. Yet, these children are largely locked out of schools, social spaces, and extracurricular activities, contributing to the 10.5 million Nigerian children who are out of school. Those who do attend school are often sidelined by not being included in sporting events, clubs, arts programs, or school leadership. They may be physically present in classrooms, but are denied equal opportunities to express themselves or pursue interests beyond academics.

Exclusion reinforces stigma, breeds isolation, and limits their future opportunities in education and employment. Furthermore, it limits the opportunity for non-disabled individuals to learn empathy, collaboration, and respect for diversity. The impact is not only human but also economic, representing a loss of a country’s GDP ranging from 3 to 7 percent. Although Nigeria has policies like the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, implementation remains inconsistent, particularly in education and recreational spaces.

To make this inclusion meaningful, the Federal Ministry of Education, in collaboration with state education boards, should develop a national framework that mandates the inclusion of children with disabilities in all extracurricular programs: sports, arts, clubs, and school leadership. This should be backed by a dedicated budget line under the Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC) and monitored through regular audits and school accreditation systems. Funding can also be sourced through a mix of public-private partnerships, UBEC allocations, and grants from development partners. Local school administrators and proprietors should be required to submit annual inclusion reports detailing participation and progress. It is only through such deliberate investment and planning that inclusion will move beyond paper policy into lived reality.

Alongside national policy, Nigeria should invest strategically in community-based initiatives that are already doing the work. Programs like the recent Lagos swimming initiative demonstrate what is possible when inclusion is driven from the ground up. These homegrown models are often more responsive to local needs and more trusted by communities. However, they remain largely invisible and poorly funded. The Federal Ministry of Education, in collaboration with state ministries and local governments, should establish an Inclusion Innovation Grant, a competitive funding program that supports grassroots organisations working to make extracurricular education accessible. Civil society organisations and private donors can also be incentivised to co-fund these projects through tax credits and public recognition schemes. Importantly, such programs must be systematically documented, monitored, and integrated into national education strategies to allow for replication and scaling across regions.

Lastly, teacher training programmes must be urgently reformed to include comprehensive training on disability inclusion, not just in classroom teaching but across extracurricular engagement. This should begin with the National Commission for Colleges of Education mandating the integration of disability studies modules into the curriculum for all teacher-training institutions. Beyond theory, trainee teachers should complete practical placements in inclusive education settings, supervised by trained specialists. Continuous professional development should also be made available to in-service teachers through workshops, certifications, and access to instructional resources that equip them to design and lead extracurricular activities for children with a range of physical, sensory, intellectual, or psychosocial disabilities. Without this structural change in teacher preparation, efforts at inclusion will remain inconsistent and superficial.

Inclusive education should not end at the chalkboard, but extend even to school extracurricular activities. We must build a country where every child, regardless of ability, is free to dream, play, and belong.

Francis Ikuerowo is a writing fellow at African Liberty. He tweets @francisikuerowo.

Article first appeared in Peoples Gazette.

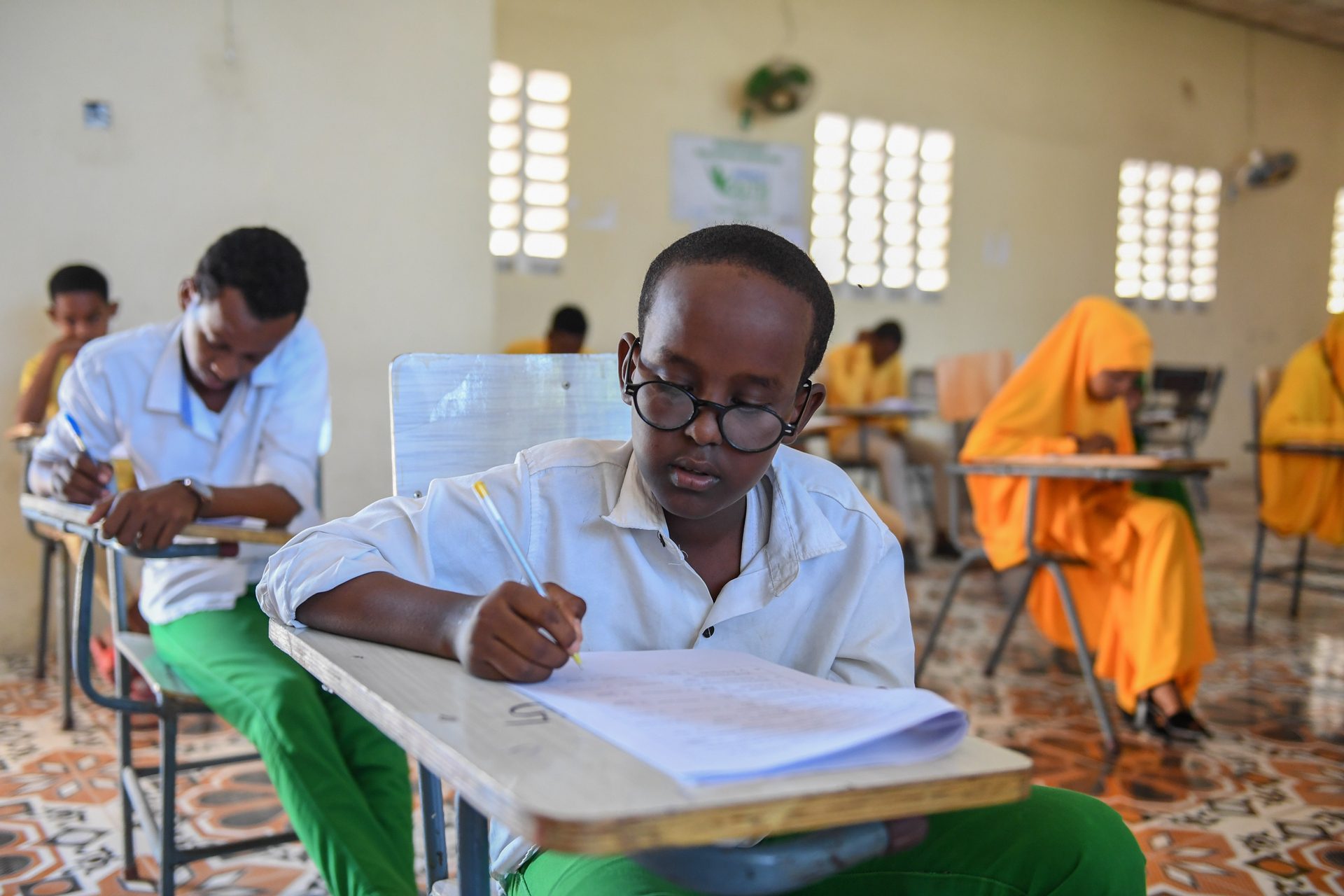

Photo by Amisom via Iwaria.